How to make yourself a better long-range shooter?

There are a lot of things you can do to improve your shooting and many of those things you can do without even visiting a range. Surprisingly, this is especially true for long range shooting. It’s hard to work on more than one or two things at one time without making everything worse, so deciding what’s the most important thing to work on first is very important.

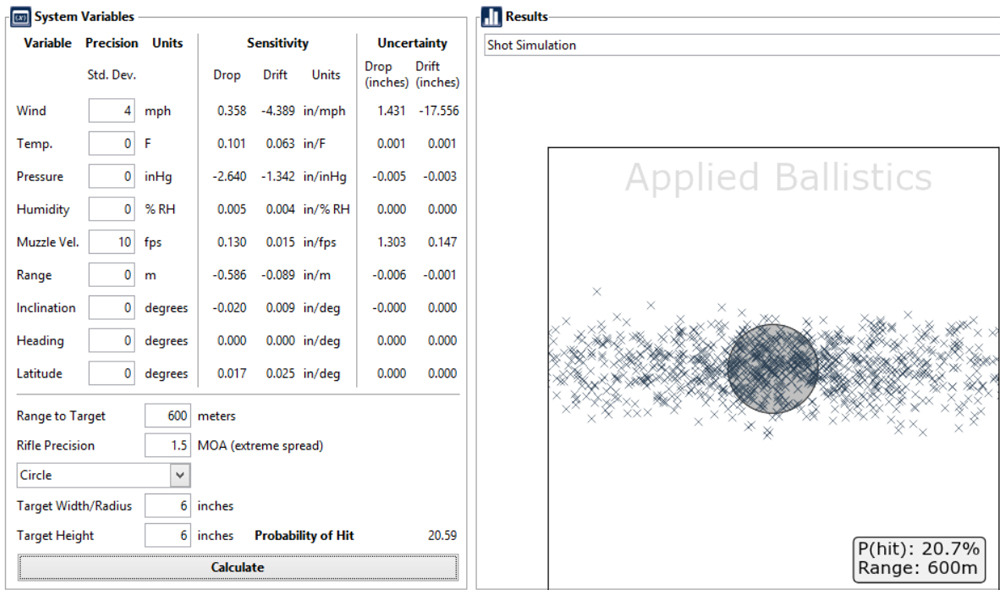

Applied Ballistics LLC is well known within the Long-Range Shooting circles. Many people are familiar with their phone App that produces firing solutions that can get shooters on target at long range with the first shot. What many people don’t know is that they also produce a program called Applied Ballistics Analytics which can not only be used to provide firing solutions but can also simulate firing shots with certain levels of uncertainty. By changing these variables in succession, we can look at what gives us the biggest gains and therefore what we should be working on to improve our shooting.

There are endless variables that can be modified in the program but not all of them are applicable to real world scenarios. For example, you can set the temperate variability to 40 degrees to simulate sighting guns in during an Australia summer day and then going out shooting in the desert at night. But this isn’t a common variable in long range shooting that isn’t easily accounted for.

The variables that we will set to 0 include temperature, pressure, humidity, inclination, heading and latitude.

Our standard shooting condition will be at -32 degrees latitude on a stationary target 600 meters away. It’s a 25-degree day, the pressure is 1013 mbar and the humidity 16%. The wind is blowing at a consistent 3M/s, or 6.6 miles per hour, from 3 o’clock. The shooter is aiming at a target that is 12 inches in diameter.

The variables we will be considering are;

Wind: How accurately can the shooter estimate wind?

Velocity: How consistent is the velocity of the ammunition

Rifle Precision: The ability of the gun and shooter to group rounds together

Distance to Target: How good is the shooter at estimating the distance to target?

| Elite | Average | Poor | |

| Wind | 1mph (0.45 M/s) | 2.5 mph (1.14 M/s) | 4 mph (1.82M/s) |

| Velocity | 10 fps SD (3 M/s) | 15 fps SD (4.6 M/s) | 20 fps SD (6.1 M/s) |

| Rifle Precision | 0.5 MOA | 1 MOA | 1.5 MOA |

| Distance to Target | 1M | 10M | 50M |

* Wind and velocity are in Miles per hour and Feet per second because, while Applied Ballistics is a 21st century company, the USA is an 18th century country.

I don’t consider distance to target a true variable – while the wind, velocity and precision of the rifle will change with every shot, the distance to target does not. You may not know the exact distance to target, but the distance to target doesn’t change between shots, like a true variable. Regardless, not knowing the exact distance to target will have a huge effect on hit percentage.

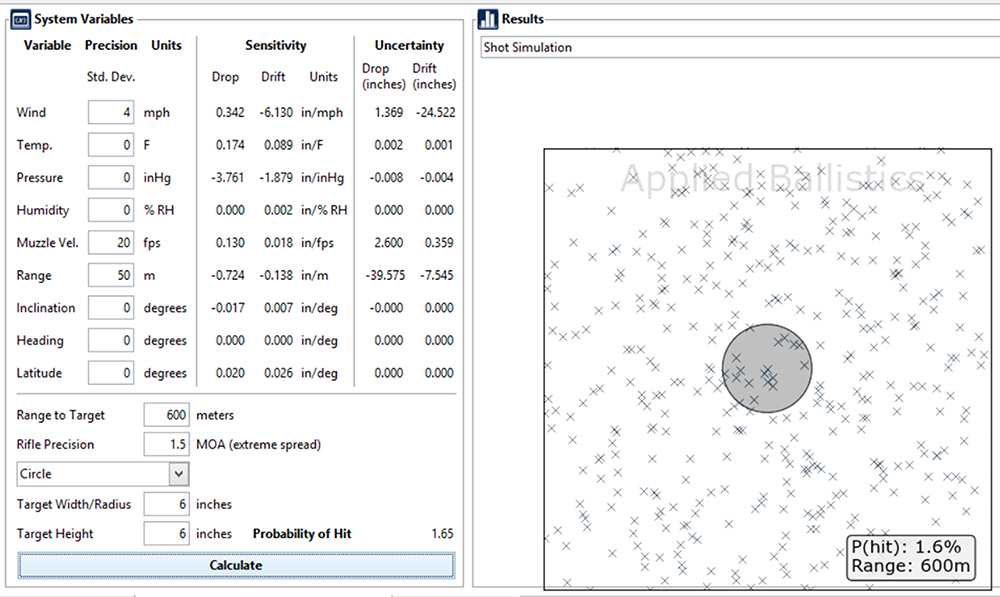

A new shooter with an average gun should be able to shoot a group at 100 meters that would fit inside a 43mm circle (1.5 MOA) (poor). Normal, mass produced factory ammunition will have a velocity spread of 20 fps either side of the average velocity (poor). A shooter not experienced in calling wind will be unlikely to consistently and accurately estimate the wind effect (strength or direction) to within 4 miles per hour of what the wind is doing (poor). The shooter just looks at the target and estimates the distance (poor). This shooter has less than a 2% chance of hitting the target.

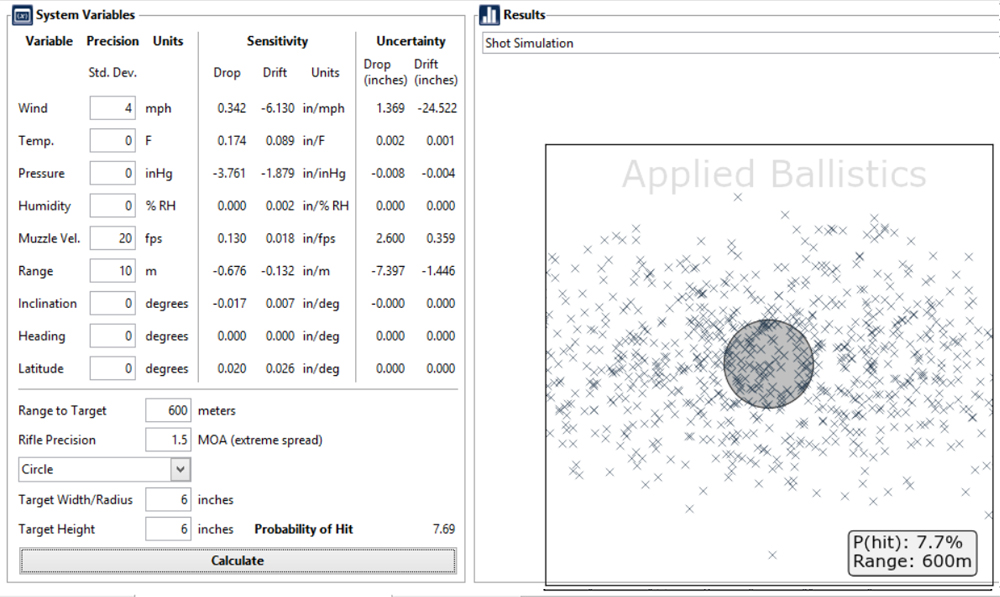

Teaching someone to use a Mill reticule to range the target isn’t hard and will get their range estimation error down to 10 meters (average). This will increase the likelihood of them hitting the target to 7.7%. Still quite low, but a big improvement over the 1.6% they originally had.

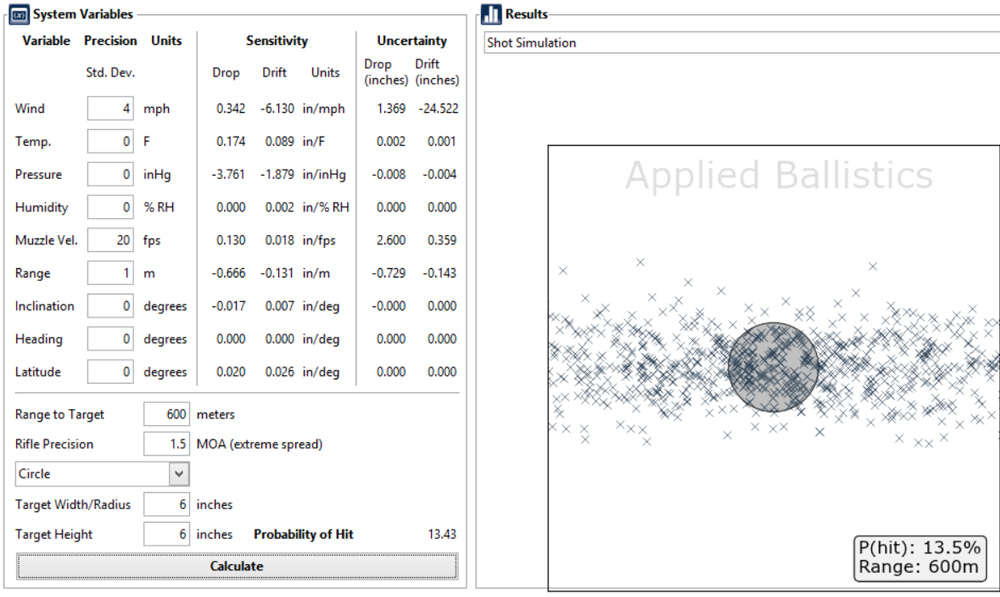

A rangefinder is even better. A good rangefinder will bring your range estimation deviation down to 1 meter (elite). This almost doubles the hit percentage to 13.4%

Looking at the three different targets you will see that, with each improvement in range estimation, the height of the group decreases. If you estimate the target being closer than it is, you’ll shoot high. If it’s further away, you’ll shoot low. The difference is quite dramatic too, so it’s very important to know exactly how far away your target is.

If you take a shot and miss, you’ll adjust for the next shot. Because the distance to target doesn’t change between shots on a stationary target and because many people shoot at known distances (on ranges, etc) I’m just going to set distance variation to 0 for the rest of the tests. But I did want to stress how important it is to know exactly how far away the target is. A rangefinder is a great way of mitigating this error.

https://beatonfirearms.com.au/shop/category/optics-all-types/rangefindspot-scopes/

On my previous blog you would have read about the advantages that bullet speed and projectile BC have for long range shooting. If you haven’t read my Reloading for Long Range Shooting blog, you can read it on the following link.

https://beatonfirearms.com.au/post_blog/reloading-for-long-range-shooting/

If this shooter started reloading their own ammunition, they could get several advantages, including;

Higher BC

Less velocity spread

Better firearm accuracy.

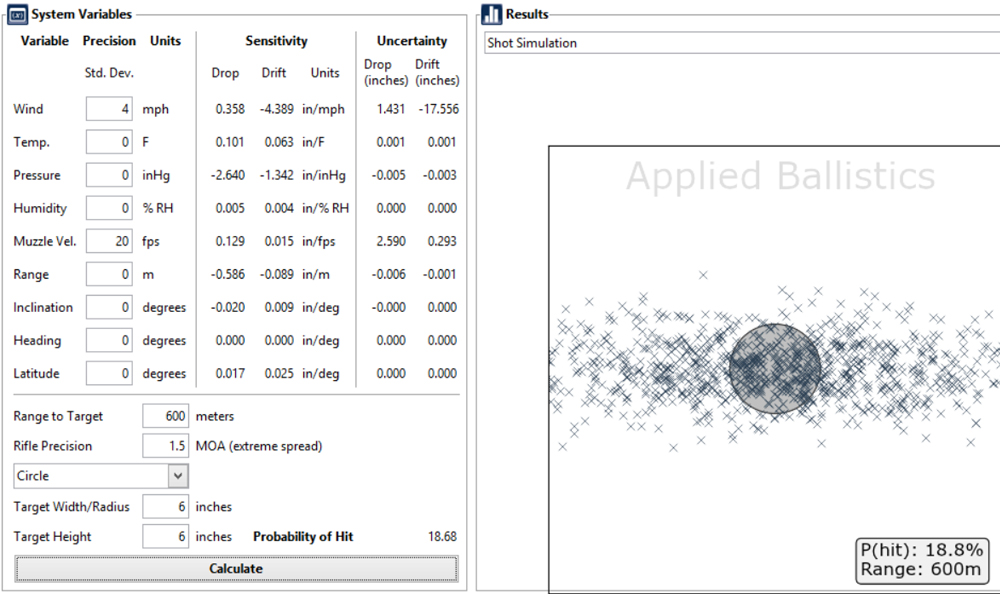

Higher BC is a given – unless you make a mistake with your reloads or choose the wrong components which cause your bullets to yaw; tumble or fly backward, if you choose a projectile with a higher BC you will get a higher BC. Changing the projectile to a Nosler Custom Competition 168 grain travelling at an average of 2700 fps will increase the hit percentage to 18.7%. We haven’t done anything with the shooters skill yet and we’ve gone from 1 in 100 rounds hitting the target to 1 out of 6.

Projectile choice is very personal. The best projectile for one person may be unsuitable for what another person wants to do. If you would like to browse through projectiles you can visit the following address;

https://beatonfirearms.com.au/shop/category/projectiles/

If the projectile choices are just too overwhelming, please contact us and we’ll give you some advice. Bear in mind that the example we are using is a competition projectile – not something you want to use for hunting larger game. But higher BC projectiles are good at defeating wind – something we’ll highlight a few paragraphs down.

When reloading ammunition for long range shooting it’s a good idea not to skimp on components. Good quality brass like Lapua or Norma have very consistent brass hardness and elasticity, meaning they ‘grip’ the projectiles very consistently. This is called neck tension. If one projectile is held tighter, and therefore has more neck tension, the expanding gases from the burning of the gun powder will build up behind the projectile, increasing the peak pressure and, therefore, the velocity. The opposite happens when the neck tension is too low. At long range, a high velocity round will shoot high – low velocity rounds low. By using good brass, and using a decent system for measuring powder, getting the spread of the velocity down to 10 fps shouldn’t be terribly difficult for a hand loader (elite). This will boost the hit percentage to 20.6%. It’s only a couple of percent at 600 meters, but just by looking at the group you can see that many out the outliners have gone and the group is much more consistent. Velocity spread has a much bigger effect at ranges longer than this example as well, so try and get it as consistent as possible.

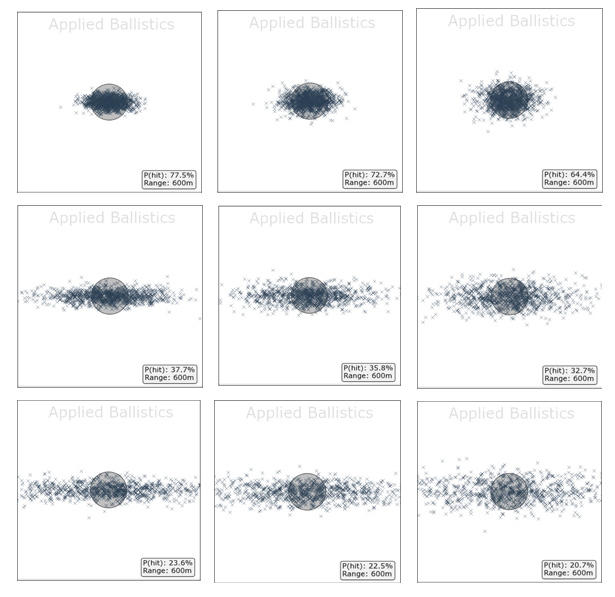

The last two variables are wind and shooter precision. Let’s look at these two simultaneously as I want to highlight an important point.

Currently we have poor gun precision and poor wind (shaded below). The matrix below demonstrates the advantages of improving each one independently or together.

| Hit % | Precision | |||

| Elite | Good | Poor | ||

| W

I N D |

Elite | 77.42% | 72.47% | 64.0% |

| Good | 37.66% | 35.76% | 32.7% | |

| Poor | 23.63% | 22.46% | 20.6% | |

If the shooter concentrated on getting their gun to shoot tighter and tighter groups through getting their gun bedded; getting a new barrel fitted; better, more powerful optics or practicing their marksmanship skills, they would have much better performance at 100 meters. This doesn’t always translate to more successful long-range shooting. As you can see by the above matrix, even if the shooter and their gun were not capable of shooting a group tighter than 1.5 MOA but had an elite level understanding of the wind, they would still shoot considerably better than someone with elite marksmanship skills and an expensive gun, but only good understanding of the wind.

Everyone wants to aim for an elite marksmanship level and an elite gun, as well as an elite ability in calling the wind. But practically, we’re better off concentrating on one thing at a time and working to improve it.

If I had a recommendation it would be – get a Kestrel first. It’s a weather meter that, as well as telling you exactly what the temperature, pressure and humidity are (all variables set to 0 in this example) it will tell you what the wind is doing where you are standing. Obviously it can’t tell you what the wind is doing between you and the target, but it’s going to give you an appreciation of what a 3M/s wind feels like; what a 1M/s wind feels like; what a 6M/s wind feels like. This is a good start to developing your understanding of wind. The other method of developing your understanding of wind is to shoot in different wind conditions and observe what happens to your projectile.

You might think that, by highlighting this, I’m doing myself a disfavor – and perhaps I am. My business is focused around gunsmithing and building custom guns, especially long-range guns. I could have manipulated these figures to say that the best decision for you as a shooter to make is to get me to build you a gun, but I thought it a better idea for me to provide all the facts so my clients can make the decisions for themselves. It’s not as though gun precision doesn’t help, it’s just not a priority as far as I’m concerned.

Once you have a good understanding of wind, I would recommend getting a gunsmith to look over your shooting platform. Bring them some targets and data do they can help you decide what modifications would be best for you.

Long Range shooting is a great sport. The best thing about long range shooting is that, as I’ve highlighted above, it’s accessible to nearly anyone with a gun – you don’t need to sell a kidney to be a decent long-range shooter. Regardless of how competitive you are; how disciplined you are; how affluent you are or how much time you have, if you enjoy shooting chances are there will be something about long range shooting that will appeal to you.