Telescopes are wonderful inventions for firearm owners – they make a target appear much closer than it is; they give a definitive point of aim for the shooter and they provide precision adjustments if the shooter wishes to shoot longer ranges or allow for wind. But do you really know what your adjustments mean and how far you need to adjust for certain conditions?

Below I’ll outline the three main types of adjustments; what those adjustments mean and who they are best suited for. But before I do that, I’m going to give a brief outline of how a rifle scope works and what happens when you adjust your turrets.

The Scope

Your rifle scope has a main tube – the area that the scope rings hold onto the scope (unless you have one of those weird European scopes with the rail underneath). Inside the rear portion of this main tube is the erector tube – this tube is what is responsible for changing the point of impact. Angle the tube down at the front to shoot higher – angle it up at the front to shoot lower. These movements are all angular, just like the change in the impact point on the bullet. That is – the further you shoot, the further the impact point will move per ‘click’.

If you adjust your scope to change the impact point of the projectile 20mm at 50 meters, it will move 40mm at 100 meters, 60mm at 150 meters and so on, irrespective of the trajectory.

- Inches at 100 yards

For a long time the most common scope adjustment was ¼” at 100 yards. Many scopes featured this measurement of adjustment as it was an adjustment system that most shooters could get their head around without any difficulty. Dials were broken up into whole numbers – 1, 2, 3, etc, to mean inches at 100 yards, with three lines in between to represent ¼”, ½” and ¾” at 100 yards.

Changing this measurement to metric, each ‘click’ should change the point of impact 6.35mm at 100 yards, although many of the cheaper scopes made in Asia that featured this adjustment system could be either side of this number.

It is simple, but it doesn’t correspond to any other system of measurement well, either linear or angular. Most scope manufacturers nowadays have gone to another adjustment scale.

- MOA (Minute of Angle)

MOA is neither Imperial or Metric, however, it does sort of correspond to the imperial system at short ranges.

One MOA is 1.047” at 100 yards, or 1.145” at 100 meters. Scope adjustments are usually ¼ MOA per click but can be 1/8th MOA on target scopes or 1/2 MOA or even 1 MOA in some short range tactical style scopes.

Scope turrets are usually similar to the Inches at 100 Yards adjustments, with whole MOA numbers broken up into 4 ‘clicks’. It is very important you check if your scope is inches or MOA for long range shooting.

If you are shooting a target at 800 yards and you know your bullet drop is 100 inches more than your 100 yard zero, with an inch adjustment scope you would adjust up 12.5” or 50 ‘clicks’. But if you were to adjust up 12.5 MOA or 50 clicks in a MOA scope your shots would land 4.7” high. This doesn’t sound like a lot, but the problem is attributing this error to the correct variable. You could ruin all your ballistic data if you get it wrong.

- Mill Radian (Mill or MillR)

Mill Radian is not a metric adjustment, though it does correspond to the metric system very elegantly. One tenth of a Mill Radian is 10mm at 100 meters.

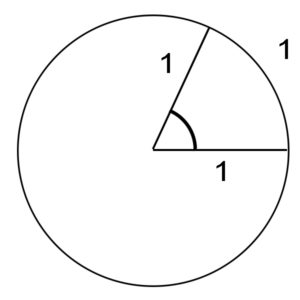

A radian is an angular measurement – please read the text box for more info

Mill adjustments correspond with Mill dot, Tactical Milling Reticule and other ranging reticules. These reticule systems are used to judge distances where a rangefinder is unavailable and for holding off for missed shots or wind.

Certainly, for long range shooting, Mill reticules are very useful. It makes sense therefore to use turret adjustments that correspond with the reticule. My personal preference for long range shooting is Mil/Mil, that is, Mil turrets and Mill reticule.

Depending on what type of shooting you do there will be an adjustment system that will suit you. One last piece of advice – if you are wanting to do long range shooting I would confirm that the turrets on your scope do what they claim they do. Scope manufacturers make mistakes and we get plenty of scopes on our Long Range Shooting courses that have a fault in the turrets – they either adjust more or less than they are suppose to. Test your turrets before working up any load data.

Zaine Beaton